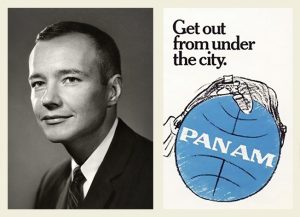

Warren Pfaff’s work yielded iconic slogans, lyrics and campaigns for Pan Am, McDonald’s and the Marines.

There are many memories of the so-called “golden era” of advertising that are conjured up expertly by Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men on AMC Networks.

Largely, it is the effort to create a world that somehow captures the excitement of an era that stood for unyielding possibility. For someone like me, who was a small child during those years, with a father who may have been a model for someone like Don Draper, the show is an inescapable reflection of just how great that era really was.

And this is why the end of Mad Men, which kicked off its final episodes—fittingly enough—on Easter Sunday, April 5 (in the Mad Men era, clothiers such as Robert Hall would have flooded the airwaves with enticements for fathers to take their sons shopping for a new suit, or two) is an indelible reminder of what we have lost along the way.

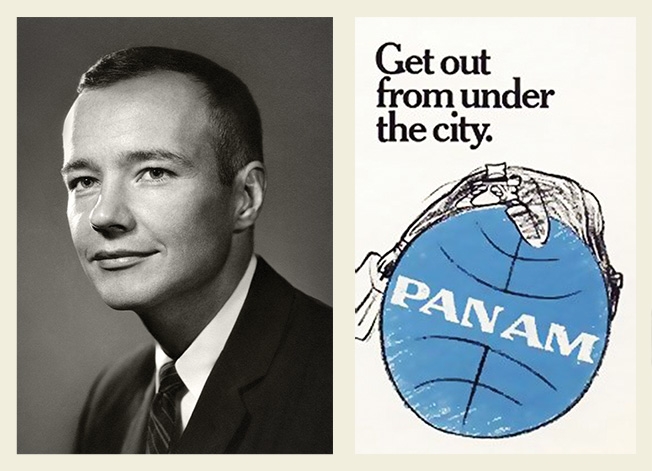

My father, Warren Pfaff, was the creative director at J. Walter Thompson, the world’s largest ad agency at the time, for most of the 1960s. It was his work that yielded many iconic slogans, lyrics and campaigns, from McDonald’s “You deserve a break today” to the Marines’ “We’re looking for a few good men” to Pan Am’s “Get out of this country … get out of this world. Pan Am makes the going great.”

Even as a small child, I was caught up in the excitement of the advertising revolution that was occurring. The sunroom study in the house where I grew up with my brother and sister was a mini-playback studio, with an Ampex quarter-track reel-to-reel deck, on which Dad’s demos and finished product were played. Dad’s return from Seattle in 1968, where he shot the original ads for the Boeing 747 that Pan Am debuted, was epic: Pan Am toy planes and other trinkets were major prizes for someone who would soon become obsessed with the Apollo missions to the moon (something captured beautifully in the previous season of Mad Men).

One of my first visits to New York City was to visit a cutout of the 747 plane that was in the Pan Am Building (now MetLife) just atop Grand Central Station (where we came into the city, from nearby Stamford, Conn.), and adjacent to the Graybar Building, where my father’s office at J. Walter Thompson was located. New York in 1968-69 was as Olympian as it could get for a small child. We were all “going places,” and it seemed that all that aggressively positive energy was somehow emanating from a place called home.

My father’s return from the Clio Awards ceremony in 1970 woke me from my sleep. I went downstairs, heard the gleeful good news of his winning an award. When he handed me the gilded trophy, I promptly dropped it on my big left toe. He spent the whole night with me, icing my toe and foot and eating Kellogg’s Corn Flakes while we listened to the radio. He had spent plenty of early mornings with me and my siblings having breakfast, after having spent the entire night working in a recording studio or making a client deadline.

Chris Pfaff, CEO, Chris Pfaff Tech/Media LLC

The Pan Am campaigns that epitomized the Madison Avenue 1960s era were a reflection of the creative power of the ad industry. Pan Am produced an album of Steve Allen’s arrangements of the “Pan Am Makes the Going Great” theme. Steve and Eydie did the song in their nightclub act, and even Sammy Davis Jr. did a hip version of the song. Advertising didn’t need to license music for ads back then. The music industry came to the ad world for its cool.

Like many in his profession at the time, my father came to advertising as a way to make a living when the theater and other creative arts proved far less lucrative. He acted with the likes of Zero Mostel and Burgess Meredith and was successful at greeting cards, but advertising was a noble endeavor with a steadier paycheck. And in the Mad Men era, advertising was a creative business, well captured in the TV show. (Although, no creative would be caught dead wearing a full suit at work. That tie was untied, if not taken off when at work, with shirtsleeves rolled up.)

My father was as much of a restless creative maverick as anyone. He left J. Walter Thompson to start Warren G. Pfaff, Inc. in 1971, launching his concept of an advertising “cartel” with a two-page ad in The New York Times on April 19, 1971, with $14,000 of his own money. He received 1,600 letters within two weeks (only one was negative). His friend and industry muse, The New York Times’ longtime ad columnist, Philip Dougherty, had given him major ink to help push that effort along.

Dad merged that firm with McCaffrey Ratner in 1990. His office at 505 Park Avenue—with a penthouse wraparound terrace—had the largest round oak conference room table I have ever seen, and standing ashtrays filled with butts were a mainstay image. He and his small band of creative and account men even built a screening room off the reception area that was state of the art. It was the scene of a company family holiday party in 1972 where the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup was screened.

My father’s last office was at 185 Madison Avenue, across from the old B. Altman Department Store. He had the last agency to have an actual Madison Avenue address, and he moved out just a few months after B. Altman had closed for good.

Dad died in 2004, a victim of lung cancer, but he was working on ads up until his death. I think that he would have loved the portrayal of the New York ad world Mad Men conjures so well (particularly the pre-1966 era).

It would be almost like going home.

This article was originally published by IndieReader.

Chris Pfaff (@pfaffchris) is CEO of Chris Pfaff Tech/Media LLC and a founder of the PGA New Media Council.

Chris Pfaff CEO, Chris Pfaff Tech/Media LLC, is a technology strategist, new media producer and a founder of the PGA New Media Council